Astonishing Hypothesis or Just Astonishing Hype?

In a recent article in Time magazine entitled “The Mysteries of Consciousness” Stephen Pinker, a psychology Professor at Harvard, attempted to explain why most neuroscientists believe consciousness is merely a quirky byproduct of brain function— what he snarkily termed “a terrifying prospect” for “ many nonscientists” because “it strangle[s] the hope that we might survive the death of our body.”

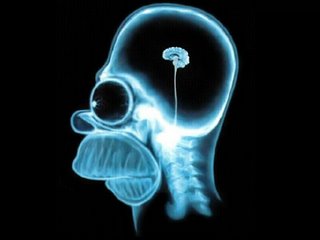

He tried to prove his point by listing various ways in which electrical probes, drugs and oxygen deprivation can produce different thoughts and perceptions in a subject, all indicating, in his mind (and apparently the minds of many of his colleagues), that “Consciousness does not reside in an ethereal soul that uses the brain like a PDA; consciousness is the activity of the brain.”

All he had really proven, however, is that he and many other academics confuse the content of consciousness with consciousness itself. The “‘astonishing hypothesis’— the idea that our thoughts, sensations, joys and aches consist entirely of physiological activity in the brain” has been old news to meditators for thousands of years.

Indeed one of the purposes of meditating is to calm the “activity in the brain” so that the sediment of thoughts and emotions can settle and separate itself from the medium it obscures and is suspended within, the translucent liquidity of consciousness. Allow this to happen and it becomes crystal clear that pure consciousness is not the activity of the brain. In fact it is best detected when such activity has diminished considerably. Stir up the sediment with electrical probes and you’ll only confuse the issue.

Pinker attempts to refute the inference of out of body experiences that might suggests that essential consciousness is independent of brain activity by briefly mentioning a recent Swiss experiment in which neuroscientists created the illusion of out of body experience “by stimulating the part of the brain in which vision and bodily sensations converge.” He dispatches the subject with a few dismissive sentences but, again, what did he really prove?

Just because you can reproduce many of the sensations of flight with a flight simulator doesn’t demolish someone’s assertion that they’ve actually flown at one time or another. And what about the fact that certain out-of-body experiencers have gathered information from places at the same moment their body was in another place? The fact that Pinker would try to palm off such wispy arguments as “oxygen starvation” as the final word on OBE causes one to wonder how much hubris plays a part in his viewpoint.

And what about the inferences of past life experiences— accounts of people who have inexplicably intimate knowledge of events and situations they could not have known about without having been someone long departed from that time and place. Do such phenomenon infer consciousness transcending brain function? Pinker doesn’t touch on such inconvenient considerations but he would probably say that such anecdotal evidence does not conform to the rigors of scientific method.

In reality the rigors of scientific method have not been properly applied to past life or out of body experience or the phenomenon of the clear light of death (see previous blog entry) or a host of other possible pathways toward a better understanding of the issue of consciousness because such inquiry is politically incorrect in the extreme to the conventional scientific community.

Is there consciousness (as opposed to brain activity) outside of physical phenomena? How do you find out if you only use instruments that measure physical phenomenon? The lack of effort by most of the scientists that claim to be interested in the subject to develop a methodology that might actually address the challenges of such an inquiry brings to mind a famous Sufi teaching story: A policeman comes upon a man searching for his key late at night under a street lamp. The officer asks where the man lost the key and the man points to a dark corner a considerable distance away. The officer asks, “If you lost it over there, why are you looking over here?” The man replies, “Because the light’s better.”

If the man was an academic required to publish something authoritative on the subject on a regular basis, I wouldn’t be surprised if he soon threw up his hands and wrote a treatise claiming that he’d proven the key a figment of our imaginations all along.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home