Don't-Know Mind

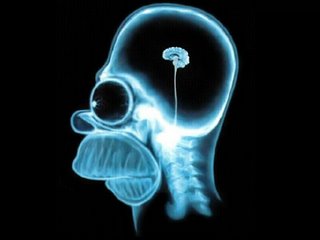

The question “Who were you before you were born?” is a fundamental koan in zen teaching. Zen masters often ask questions like, “What does your original face look like?” or “Where have you come from?” Of course, one of the purposes of such questions is to jog the initiate out of cursory answers like, ”I’m a professor”, “a mother”, or simply a flesh-and blood automoton of electrochemical stimuli and responses.” etc. Because beyond the thoughts and emotional responses and fleshy parts, there is that unknowable essence known as pure consciousness, sky blue mind, The eye beyond the “I” found outside the realm of questions and answers. The silent witness transcendent of conditioning and assumptions. What the masters call “don’t-know mind.”

Zen Master Seung Sahn said our purpose in this existence is to understand “don’t-know mind.” We don’t do it by reading a bunch of books which are limited to the opinions and dogmas of others but by dwelling in “the primary point” “before thinking”. “Keeping a don’t-know mind 100% you and everything are already one.” he said.

Easier said than done, of course. Even in my deepest meditations my babbling brook of constant thought actually subsides into a pool of stillness only for a moment or two. And yet, to borrow a metaphor from Majarishi Mahesh Yogi, it only takes a moment of dipping the cloth into the dye to change the cloth indelibly. Then you hang the cloth in the warm sun of the everyday world where it fades somewhat. Then dip it in the dying vat again before exposing it again to the heat of the light of day. Repeating this process over and over, the color deepens and becomes fast.

Satsang (sitting meditation) is not the only path toward don’t-know mind, It also helps to contemplate what we aren’t— a process that Krishnamurti calls “negation.” One thing becomes clear. We aren’t our thoughts. And once we come to this realization, we are forced to eliminate all forms of conception from our definition of self or anything else really. Soon one realizes that, since any definition can only be a product of thought, any attempt to capsulize consciousness into a concept is futile. All concepts, words, symbols, and ideas about observers and the observed are but maps, not the territory— as alien to the true nature of the thing they describe as a four color atlas is to the vast stretches of complex terrain it vaguely refers to.

Seung Sang points out that when a dog barks Koreans say he makes the sound, “Mung! Mung! Mung!” Japanese people say it says, “Wong! Wong!” Polish say it’s “How! How! How!” and Americans say it’s “Woof! Woof!”…”But this dog never gives his sound a name; he only barks. Human beings make this word and sound an idea, and become attached to it. Then they cannot see the world as it is.”

So if you ask me to describe my original face, my answer is, “How! How! How!”